Jack was born in the two-fisted, blue collar hamlet of Williamstown, New Jersey. In the pre-television days of sports heroes, his parents would name him after their favorite heavyweight boxer. He was the youngest of four brothers and a sister whose childhood days would unfold against the hardscrabble backdrop of America’s Great Depression.

In a time of great sorrow and hardship for the nation, Jack’s family would not prove the exception. He would later speak of the embarrassment of going to school with cardboard in his shoes to cover the perforated soles. Some days his mother would busy herself in the kitchen, glancing frequently out the window. If she began to hum, the mood in the house would brighten because it meant she had spied the boys’ father approaching with a loaf of bread or other welcome staple. In a country having lost its prosperity, Jack’s parents did what they could for their family. Ironically, in a conversation decades later, Jack and a brother would agree that those simple days with their parents were the happiest of their lives.

It was a different time.

Township rivaled township with local “gangs” resolving their differences with their fists. This was the case when Jack and some other boys traveled to a dance in a neighboring township. At an agreed upon signal, the first notes of a song on the jukebox, fists flew. Contemporary consensus was that Jack’s group scored a victory that evening.

Possessed of a hair-trigger temper as well as remarkable reflexes, hand-eye coordination and speed, Jack proved a skilled boxing adversary. This ability would later lead him to a sparing bout with one Walker Smith, an extraordinary athlete who would become known to the world as Sugar Ray Robinson.

But medical technology in the early part of the twentieth century was not what it is today and eventually the family found itself without the sagacity, security and guidance of the parents.

Rudderless, Jack’s adolescent mischief would earn him a stint in reform school. It was there that he would learn a skill incongruous with his flash-temper personality. Years later, his home would be decorated with intricately woven and beautifully adorned macrame hangings made with his own hands.

Spawned by the onset of World War II, a wave of nationalism swept the country carrying Jack and his brothers along with it. Enlisting in the Army Infantry, he took his basic training at Camp Forrest, Tennessee. The war years would find him parachuting into Normandy with the 82nd Airborne Division to liberate Sainte-Mère-Église. He would be felled by a ricochet in the Ardennes Forest during the Battle of the Bulge. In later years he would tell of the medics’ efforts to keep his exposed intestines from drying by pressing wet rags against the wound.

Jack would survive his battle injuries and the war. His older brother Nelson, a swarthy, handsome man with a striking resemblance to actor Gilbert Roland, was decreed a different fate. An air burst during fighting in the Colmar Pocket bore his number. He rests with his fellow soldiers in the American cemetery at Épinal, France.

Williamstown would honor the sacrifices of its sons. A monument with their names was erected in the center of town. It stands yet today.

Jack would re-enlist. In the Army he had found a home, a surrogate for the hearth he had lost so young. He would one day list the order of his loyalties as, “My country, the Army, my family”.

It was a different time.

Now a military policeman, Jack found himself stationed in Nuremberg, Germany. There he met a slender young German girl, a model, who left him breathless and would steal his heart.

Wilhelmina Weigel, just 17, was possessed of a stylish air with the carriage of a princess and looks that quickened the pulse of any man within sight radius. Her father had fought for the Wehrmacht on Hitler’s Eastern Front. He had been killed after the war, just outside the family residence, when an American tank had accidentally discharged its main gun.

Wilhelmina’s mother disapproved of this man, this American. After all, his side had been the enemy. But with the stubborn streak that served to enrich a decidedly feminine personality, she continued to see him. Jack and “Wilma” had backgrounds vastly dissimilar, yet they proved a perfect match. Their experiences and personalities both conflicted yet complemented each other. Each of the unlikely couple’s fascination with the other would prove timeless. They married, and she bore him a son.

Jack had found his niche as a soldier. A natural leader, he embraced the structure and discipline of Army life. He learned well what was expected of him and how he must perform his duties. He was the man to beat in the Battalion Soldier of the Month competitions. His methods, though at times unorthodox, were effective.

Such was the case when he was detailed to check the papers of a trainload of 101st Airborne troops returning from weekend pass. The soldiers were in various stages of inebriation. All was proceeding smoothly until one man took umbrage at being disturbed and responded to Jack’s request with a curt, “Go to Hell”. Jack repeated his request, and the soldier replied in kind. Jack, turning as if to move on, instead suddenly spun around with his baton in hand and caught the soldier across the nose with the club, knocking him to the floor of the car. Spewing blood from his nostrils, the soldier produced his pass. Jack encountered no further problems.

The high esteem in which Jack’s abilities as a soldier were held by his superiors served to buffer any potential damage to his career that his quick temper might have caused. One altercation in the barracks left the ceiling spattered with blood. He once said that there were times his temper probably saved his life.

This could well have been the case in Berlin in 1956 when fate dealt Jack a hand no one man should have to play. He had stopped in a cafe for refreshment when, for reasons now lost to time, a disagreement ensued between Jack and a German patron. Off duty and determined to stay out of trouble, Jack turned to leave. The German would have none of it. In an act reminiscent of a movie he picked up a metal legged chair, swung it high in the air, and brought it down on Jack’s head.

But this wasn’t Hollywood. The chair didn’t splinter into pieces and the man that went down beneath it got back up. What happened next would be forever carved into the memories of those who witnessed it. One woman would later tell investigators that she had seen many fights in American westerns, “…aber so was nie mals”, but never anything like this. Jack would walk away at the end of the melee, leaving five men – and one unfortunate waitress who had come through the kitchen door at the wrong time – on the floor in various levels of consciousness. He had bodily thrown a sixth man through the cafe window.

Jack’s chain of command would intercede with German officials on his behalf. Excepting the stitches required to close his scalp, he would escape serious consequences. The city of Berlin, however, was placed off limits to him. Any personal business that he might have there in the future would be conducted in the presence of a police escort.

Integrity and forthrightness were qualities he both admired and exhibited. Assigned to Fort Knox, Kentucky, Jack took advance pay to defray expenses while moving his family. When the entire advanced amount was deducted from his next paycheck, he found himself unable to provide food for his family. As they drove to a small off post grocery store, Wilma asked him what he had planned. Jack stated simply that he was going to ask for credit. Wilma smiled, “You won’t get anything.”

Jack explained his situation to the store owner who said, “Take what you need, Sarge. I’ll see you on payday.”

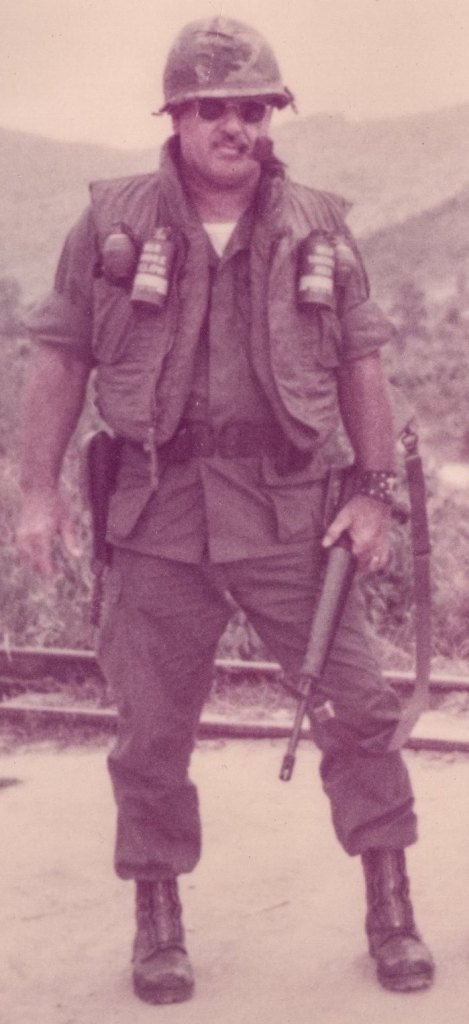

Jack would heed his country’s call to arms again, shipping out to the Republic of Vietnam in 1970. There, the concussion from a Viet Cong mortar would leave him unable to catch his breath. Diagnosed with the onset of emphysema, he was medevaced back to the United States. The Army he had served so well then medically retired him with twenty nine years of service. If he took care of himself, his doctor said at the time, he would live another twenty years.

Jack Dempsey Darrow, my father, died on March 5, 1991. A scrapper his entire life, the fight against his lung disease was a battle he knew he could not win. But he kept swinging. He engaged in his beloved pastime, hunting, at every opportunity. He and Mom entertained whenever possible and built a strong circle of friends. Retiring in Arizona, he built the dream house he could never have while living the rootless life demanded by the Army. Answering the door to strange children selling chocolate bars, this war hero opened his wallet to “the little snot noses” with a smile and would then have to make a trip to the bank.

Funerals are for the living. My father’s was a model of military precision. He had been squad leader of several Honor Guards and the one detailed for him from Fort Huachuca would have made him proud. From the rifle volleys to the passing of the Flag to my stoic, respectful mother who mouthed a silent “Thank you”, they were letter perfect.

But there are limits to what a person can hold inside. One rainy night outside Dallas I could drive no farther, my eyes overflowing with words never spoken and others better left that way. For all the I Hate You thoughts for sending me to my room, the I Wish You Were Dead thoughts for grounding me, all the thoughts, words and deeds that shamed me now, I could no longer atone. I could not simply pick up the phone and say, “I’m sorry”. The Thank Yous never spoken for actions casually taken for granted now stuck hard in my throat. Slowly, inexorably, the awful realization dawned that the void left by his passing would never be filled. Go, I told myself, before the police stop to see what’s wrong. But it would be the better part of an hour before I could once again gain control over myself and my car. Thank you, Lord, for having given me the maturity to drop the macho facade and say to this wonderful man, “I love you, Dad”.

Holidays are still difficult. The man who made Christmas so wonderful for a bright eyed son and doting wife lights our lives no longer. And there is always the granddaughter who bears his name, whom he never met. She knows him only from his pictures and the memories of those whose lives he touched.

And so we laid him to rest outside Phoenix, in the Sonoran Desert he loved so much, where the quiet of the evening is broken only by the howl of the coyote as he serenades the moon. Where the Roadrunner, the bird whose ruffled head feathers “make him look like he just got out of bed”, passes quietly by on his appointed rounds. Where the snake glides effortlessly across the evening sand. Where there is the celebration of life.

He was never a big man, standing a bit under 6 feet tall and weighing 190 lbs. in his prime. But he once walked large across this land and men would step aside to let him pass.

My father, my mentor, my friend. I learned from him to not confuse celebrity with greatness.

Coming of age during a time when this nation poured into the streets in a desperate search for heroes, I was truly blessed. You see, one lived right down the hall.

I Love you, Dad. Happy Father’s Day.

Your son.

Your dad was a real hero and you are a good son.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dempsey, your tribute to your father is colorful, rich, and moving. I knew you were writing about your dad early on. The signs were there.

In many ways, your father reminds me of my father. The Army became his “surrogate,” as well. Raised in a Rhode Island blue-collar town largely comprised of Portuguese immigrants, he did not learn English until he went to school. The transition was hard. He fell in with the wrong crowd who dubbed him “polecat.” He was a Golden Glove boxer who fudged his age to join the Army when he was 17. In Germany, he met my beautiful mother, Ingeborg. He served his country honorably in Vietnam. He was a lifer, a soldier’s soldier who turned down a commission. He taught me everything I know about working hard and doing without. He was a tough guy. He was my hero.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Charmaine. We were both blessed. Your love for your father is obvious. Wherever they are, let’s hope they’re laughing, swapping stories, and downing a couple of cold ones.

LikeLike

Indeed, Dempsey! Let’s imagine they are enjoying themselves. Imagine the stories!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was a very moving tribute and story of your dad. Not many of current friends can say what I am about to . I had the pleasure and honor of knowing both your dad and mom. Oh I can remember him enjoying a puff on his old pipe that he loved so much. I can even remember carrying your mom’s groceries from the commissary up the several flights for her. More than any memory I can remember, I call their son my friend. Happy Heavenly Father’s Day Sergeant Darrow Sir and Rest in Heaven.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Randy. Many great memories. My folks always thought very highly of you. We’ve remained friends for a long time and knowing you has always been a blessing.

I hope all is well with you and yours.

LikeLike

Dempsey, this tribute to your dad brought me to tears.

Beautifully said. I am sorry I never got to know him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

At least you got to meet him.

LikeLiked by 1 person