The big Oldsmobile Vista Cruiser Station Wagon moved silently in a world of white. Conspicuous by its motion in a scene of winter still life, its three passengers rode without speaking in an atmosphere reflecting the moody gray of the overcast sky.

With a slight turn of the steering wheel, the driver turned off West Point’s Cullum Road and down a sloping, narrow lane angling toward New York’s Hudson River. Thickly muscled forearms worked gently with power steering to guide the heavy car across patches of ice with an artisan’s skill. An over-steer, or too heavy a pressure on the brake, and a collision with the rock restraining wall would grind metal and scrape paint.

Slowly the driver brought the car to a stop. The three got out and stood for a moment, all eyes trained on the frozen Hudson. Bus-sized boulders of ice lay strewn about an alien landscape scarred by deep fissures and unseen crevasses awaiting the careless and the adventurously foolhardy. On the frozen river, as on the land flanking it, nothing moved.

Then the passenger who had been riding in the back seat pointed.

“There!”

In the surreal landscape of ice, nothing was immediately recognizable. Then, slowly, a shape in the distance could be discerned, its darkness contrasting against the surrounding alabaster.

The driver opened the rear door of the car and retrieved a hunting rifle. He opened the bolt of the .30/06 and removed the lens caps from the telescopic sight. Next he took a box of ammunition from the glove compartment and made his way down the slope toward the river. When he reached a spot that afforded an unobstructed view, he seated himself in the snow.

The passenger who had made the sighting now peered through binoculars.

“I’d say, oh, four hundred to four hundred fifty yards, sarge.”

The driver loaded a cartridge into the rifle’s chamber, the sound of the bolt seemingly amplified in the silence of the cold air. His movements now were mechanical, though measured. They were what he’d learned long ago and had taught countless others: acquire the target, take a deep breath, let it all out, take another, let it out halfway, hold, now start your trigger squeeze…slowly…gently…

The bellowing report of the rifle shattered the stillness with the abruptness of a sledgehammer smashing crystal, the rolling thunder of its echo taking a few seconds to return from the river’s far bank. Simultaneously with the shot, chunks of ice were seen to spurt high into the air, the result of the bullet striking with more than a half ton of destructive energy on the near side of the target.

Now the distant shape moved and in so doing identified itself, features that before were unrecognizable were suddenly familiar. It was a deer. All four legs had lost their grip on the ice and were splayed out to its sides as the animal lay on its belly. Her legs flailed frantically as the doe made a fruitless attempt to remove herself from what instinct told her was danger. She had been in that position on the ice for at least two days.

“Short, sarge”, binoculars was saying. “I’d say, on a line, about, oh, fifty or so yards…”

The rifle’s second blast cut him off. Immediately the doe’s side turned a bright crimson and its head dropped to the ice. Then, slowly, the head came back up and shook, like a horse shaking water from its mane, and, just as slowly, lowered. The deer would not move again.

“Damn! She’s bleedin’ like a stuck pig!”

If the driver heard the remark he gave no sign, he was already halfway up the slope to the car.

*****

My father was First Sergeant of the Military Police detachment at West Point when he fired the shots on that cold day. His shooting position had been within shouting distance of where he’d provided security and traffic control earlier that year as Bob Hope had been presented West Point’s prestigious Thayer Award.

I had been there when the phone rang and although time has robbed my memory of the caller’s identity, I recall my father’s responses, “..two days?…what about a flat-bottomed boat and a lasso?…what else has been tried?…alright…roger, understood…”

He was a man who had hunted his entire life. Deer, rabbits, quail, elk, black bear; all were pursued, many were harvested. Much has been written and debated about the primordial drive that casts us in our primitive roles as predators and sends us into the field in pursuit of prey. In effect, the hunter does what those who do not hunt have others do for them: like his pre-Safeway predecessor, the hunter kills his own food.

The hunter knows that the prey will not give up its life easily. He knows that instinct, superior senses, and sheer physical ability will combine to make the end game difficult for him, if not impossible. He may keep trophies of the hunt to remind him of the experience. He knows the difficulty of the pursuit, where both predator and prey act out their predestined roles. He knows that by dying the prey gives up the stuff of life to the hunter. And this he respects.

But what happened on the Hudson River that day was not a hunt, it was simply a killing. There was no matching of intellect against instinct, perseverance versus speed, preparation against brawn. There was no adrenaline charged moment of truth with the prey in full flight and the hunter challenged to effectively perform a split-second harvest. Death had been meted coldly with the practiced efficiency of an executioner.

Nor were my own hands unbloodied. In the interest of saving money, I had begun handloading ammunition. I had painstakingly assembled the components that would become the instrument of this hapless animal’s death. The only mitigating factor that might pardon my conscience was that what was done had been done to end the deer’s misery.

This fact is the single justification for what took place, but it is sufficient.

At the hot climax of the hunt, the kill is made as efficiently as possible. No hunter enjoys seeing an animal suffer. No hunter is unmoved, undisturbed, at the moment of the kill.

It is said that nature is harsh; watch any of today’s animal documentaries to see the awful truth of this statement. Though hunters themselves belong to the natural world, they are separated from wild predators in that they care about their prey and do everything possible to relieve it from suffering. Those who kill with dispassionate detachment have become another kind of animal, a human that is simply a killer.

I welcomed my father’s reaction to this episode. It confirmed what I already knew, that this veteran of two wars who would not consider taking a gun-free excursion into the woods may have been a hunter, but he was not a killer.

I would go on to become a Cadet at West Point. On occasion I would find myself near the turnoff from Cullum Road, the slope that led to the site of a distasteful event from years before, an event that would haunt those who were there.

I have hunted in the past. Some hunts are more memorable than others; some have faded almost completely from memory. But the vision of a little deer that was killed on the Hudson River remains as crisp and clear as the air of that winter’s day.

—

Dempsey 🌵

Thank you for sharing this poignant moment, Dempsey. Your descriptive imagery places me there at the scene. What a tribute to the memory of an honorable man. Do you remember reading “The Most Dangerous Game?” What a companion piece this would be.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve heard of it. I’ll look it up, thanks.

LikeLike

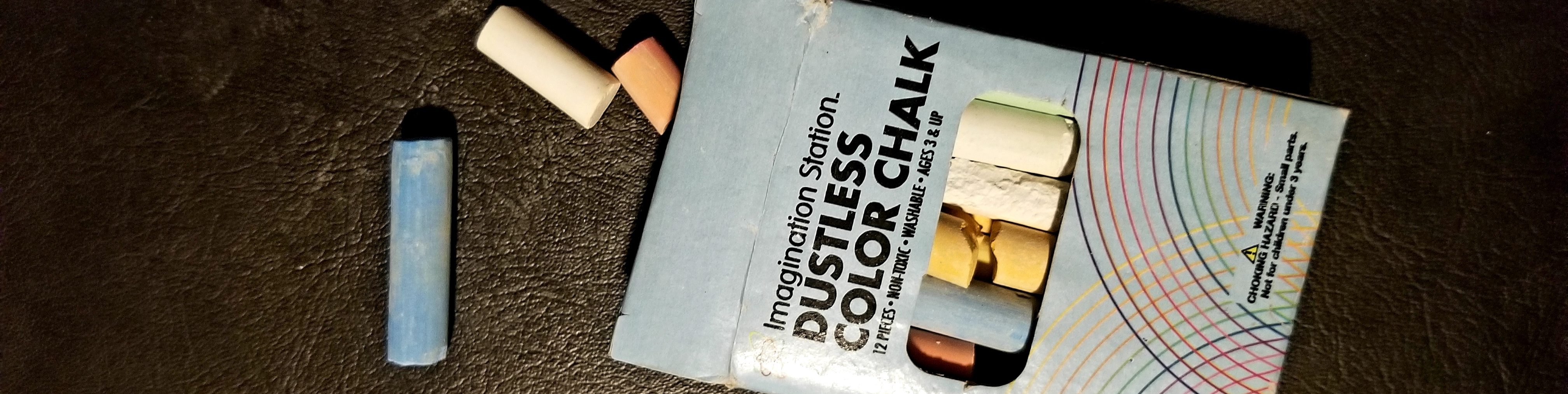

BTW, to answer a question, the picture is of my father’s .30/06.

LikeLike

Got it! We are flying to Phoenix on the 2nd of March. We will have the 3rd or 4th available to see you and Peggy if you are interested and a available.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice job Dempsey. Very well written!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Ruth.

LikeLike